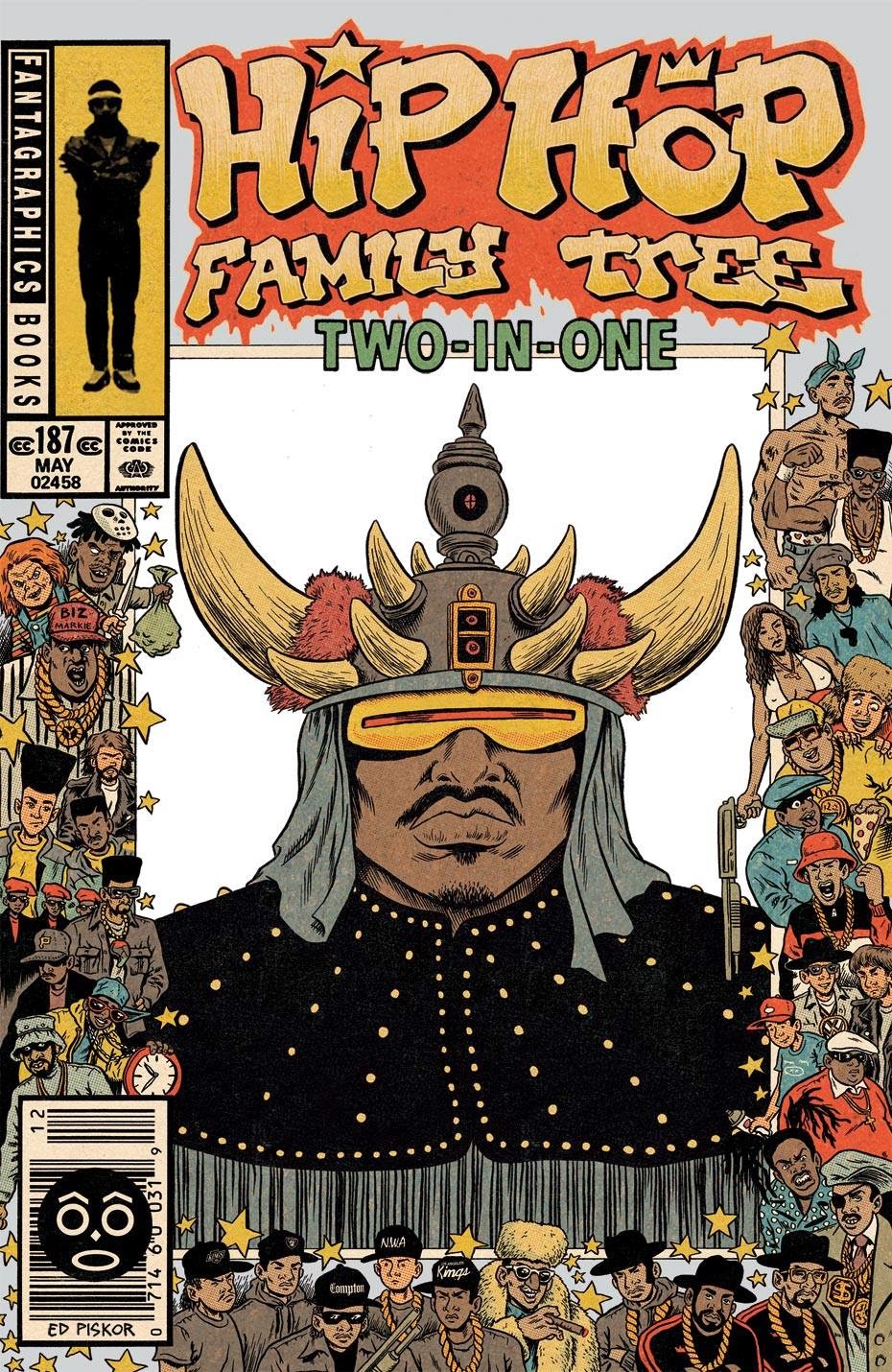

History should have the force to slap you smack in the face, seeing your body hit the pavement hard, and then it spits in your eye just when you thought it was safe to look. In my history classes I try to teach history as a full on onslaught onto my student’s senses. History losses some of its brute force when put down to paper, where the writing is so think and dense that any student could get lost. However, there have been new methods of presenting history to the masses which holds both the education quality as well as entertainment value. In the realm of Hip-Hop it is even more pressing to show these new methods of history writing, and even presenting history. Hip-Hop is so tightly bound to our veins at this point that its origins have reached a critical mass of mythology. These stories of the early generation of Hip-Hop innovators are so far fetched, amazing, indecipherable (try to read Russell Simmons or Alonzo Williams’ words), that they can only be shown in a particular form. Many blog posts ago I reviewed the comic/history book written, researched, and illustrated by the great Ed Piskor. The first volume took us back, via the Deloreun’s boost from the flux capacitor, to the late 1970’s and ending in early 1981. For the details please refer back to that review, but for now it’s time to sink our teeth into volume 2!!!

Like the first volume our humble director of traffic, in the guise of Ed Piskor, leads us through these amazingly colorful corridors. He recounst many key events in the history of Hip-Hop, as well as the many fascinating side comments, far-out factoids, and some comedic side notes, as well as one or two tragic. It all begins with the story of Doug E. Fresh and how he was discovered in his native Harlem neighborhood by the one and only rapper by the name of Spoonie Gee. Spoonie, who was Doug E.’s neighbor, according to the story presented shows him his talents, as his beatboxing skills are reinterpreted through the wizardry of comic book wordings. With larger than life lettering you see the “BOOM BOMP, BA-CLICK OOMP!” coming out of Doug E.’s mouth. The entire pages, and its panels, show the skills as they waift through the crowd and eventually get to Spoonie’s uncle, and owner of Enjoy Records, Bobby Robinson.

The book continues to overemphasize the lyrics, by making them loom large over the rest of the cell that is trying to contain these words. Another fine example, displaying the sheer energy of the words, is see through the eyes of Malcolm McLaren being introduced to the Zulu nation in the Bronx River Projects. The words “Zulu Gestapo” loom large, as the cell provides the feel being somewhat askew and distorted. The cells on the page are shaky, which is probably how you felt in the midst of the chaos of dancing and fighting while the speakers are on full blast, shaking your kidneys from side to side. Piskor is trying to show us the energy of these jams, and the magnetically beautiful chaos surrounding these parties.

There are many more references he uses, as well as overlying themes about the music and its culture, as he fills in details of known stories. One theme he uses, through the connection with Rick Rubin and the very young Beastie Boys, is the connection between Rap music and Punk music in the early days. This volume spans from the years 1981 to 1983 where both genres had the same connective tissue of do-it-yourself, while eschewing the conventional sounds. It was Rick Rubin who brought that idea to rap, which would forever change the way artists recorded rap music after Def Jam came into existence. The Punk aesthetic isn’t lost on the readers as Piskor shows us how these worlds collided at times into one.

The Punk aesthetic isn’t lost on the readers as Piskor shows us how these worlds collided at times into one. Other examples of this include the clubs themselves in the downtown Manhattan scene, which included the Hip-Hop heads and the Punks.

Piskor is also very aware of the earliest days of Hip-Hop and how DJ’s who would play records would have to play breakbeats as rap wasn’t being recorded yet. Early rap recordings had live instrumentation, akin to the Disco sound, where the performance became obscured by an older form of recording songs. One of the very crucial elemenst to the brith of Hip-Hop is the emphasis on the DJ, and how famous DJ’s like Kool Herc, Flash, and Bambaata dug deep for obscure up tempo songs, or at least a small section of the song that people can dance to. Piskor, being an amazing researcher as well as illustrator, shows this with a quick backstory to one of the most popular songs equated with the era, the Incredible Bongo Band’s “Apache.” He traces the origins of the song to its creation by Jerry Lordon of the Shadows,

to its later incarnation by the Bongo Band,

how it went into obscurity and remained there until DJ Kool Herc began to play it at his parties. Many groups sampled it for their songs including an instrumental track Grandmaster Flash concocted and released by Sugar Hill Records. This is another example of Hip-Hop culture’s far reach into the past, and not necessarily an exclusively black past, but rather a shared musical past.

He also attempt to show how raw some of these rap groups performances were as opposed to their recorded material. One of the best live performaces of the past, and a dear personal favorite of mine, is Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five’s live rendition of “Flash to the Beat.” Interestingly enough Piskor shows that they were invited to perform live at the Bronx River Projects by Afrika Bambatta, with the help of a new gizmo Flash recently acquired he called a beat box, but was actually a drum machine. In the book Piskor notes a cloud over Bambaata as he says to himself that he was, “glad I’m recording this…” Here’s a version to listen to,

This is a perfect time capsule showing us how great these guys were when performing live. Apparently, according to Piskor’s account, the tape was leaked (either through theft, commerce, or trading) and circulated throughout New York City. It’s a treasure of a primary source because you hear the call and response between the members of the crew, capturing this moment of time that was lost for good. Piskor wrote it best saying that, “The bootleg (talking about this recording) is a multi-generation duplicate. It’s gritty. You can hear all sorts of residual noise. It’s far from perfect, but it might be one of the greatest snapshots of Hip Hop Before the music became bis business.” (Page. 34).

I will not recount the stories, cause you should check them out on your own, but Piskor also has a gift in showing many things through these images. Not only are we seeing a story unfold, we’re also seeing other themes and trends that Hip Hop both created, destroyed, or compromised. One of these themes is the generational divide within the African-American community when it came to rap music, both recording and playing it on the radio airwaves. There are many telling scenes speaking of this divide, and even negative attitudes held by the older black generation towards this new music. He cites one of the most popular DJ’s, Frankie “Hollywood” Crocker (Note that DJ Hollywood took his name from Crocker), saying that there was no money in it due to the kids being broke. Another example is the exchange between the Furious Five and a disgruntled baseball player, Willie Stargell, and how he berated them for using nasty language while grabbing themselves onstage.

First the great, and Piskor makes sure to show his immense presence, Melle Mel chimes in saying that that is exactly what they are, while the group all chime in saying (with bold letters) “We Nasty!”

Hip-Hop history has short arcs as well as long arcs spanning years, even decades. The book is very well balanced showing the specific stories happening at that specific time frame, like the creation of the first Hip-Hop film, Wild Style. These little stories form the details about the history of the early years of Hip-Hop, and recorded rap music. However, Piskor also foreshadows stories or begins them and then stops in order to keep the avid fan waiting for the rest of the story. He does this with groups like Run-DMC and the Beastie Boys and how they evolved from scrappy youngsters meeting the people ( or in the case of Run-DMC being related to) who would jump start their careers. Piskor is also not fixated on the east coast as he does the same with up and coming artists, who are just getting their first taste of success, like young Dr. Dre and DJ Yella, and Ice-T. Interestingly enough the end of this volume show us the start of what we know as the group Run-DMC and the start of Dre’s push to the limelight.

Also, speaking of Dre and Run-DMC, Piskor shows us how Run-DMC’s performance in 1983 at the Cali club Eve After Dark influenced Dre immensly. They only performed for ten minutes, but those ten minutes were hard, raw, and packed with stripped down rage. Piskor writes that Dre says that, “I wanna make some street level shit like them dudes.” While Dre was being influenced by Run-DMC, Chuck D. and his mobile DJ group called Spectrum City pop up from time to time. He was briefly featured in volume one, and in volume two we get a sense of the type of music influencing his ears. He was far more politically inclined, as most rap music was far from political, so he gravitated towards these songs. There are not many but Piskor points them out beginning with Brother D with the Collective’s song “How We Gonna Make the Black Nation Rise,” and of course “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five, and in this volume the reworking of a Malcolm X speech by the session musicians at Sugar Hill Records. Keith Leblanc, along with Doug Wimbish played over the words of the late Malcolm X. The song faded quickly from the radio, but certain ears heard it. One pair was that of Chuck D.’s, and after seeing how black youth have forgotten Malcolm X he decided to step in and make sure that brothers are gonna work it out.

For all us Hip-Hop history lovers we all know what will happen next. However, I can’t wait for Piskor to guide my vision in that realm.

Peace

#EdPiskor #HipHopFamilyTree2 #HipHopFamilyTree #Apache